The Henry Gorski Retrospective

The Gorski Retrospective highlights the conflict resolution process binding an artist's canvasses of a lifetime into a formal and meaningful progression, as diversity into a dialectic continuity. It validates the conflict resolution process, which provides greater insights into an artist's works.

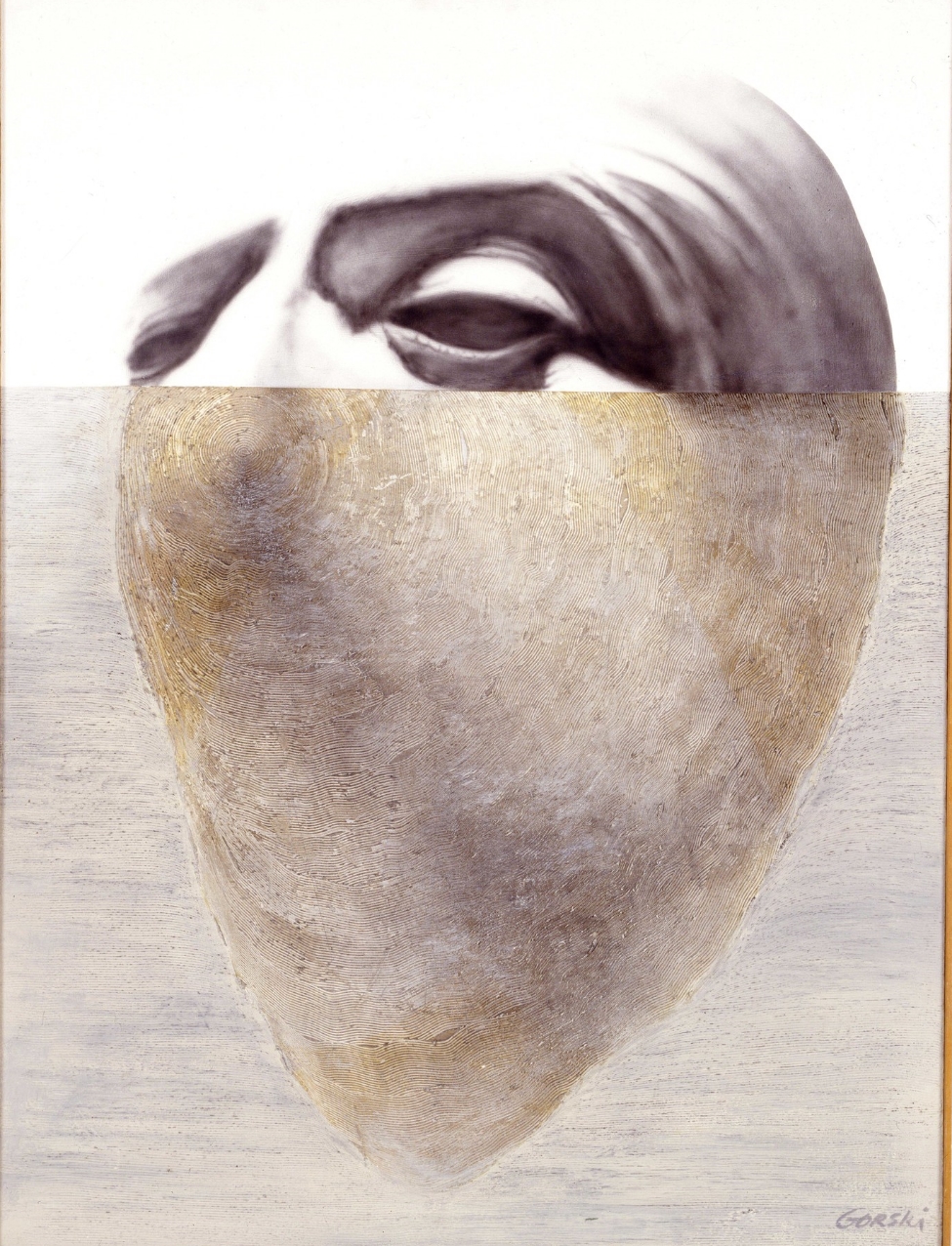

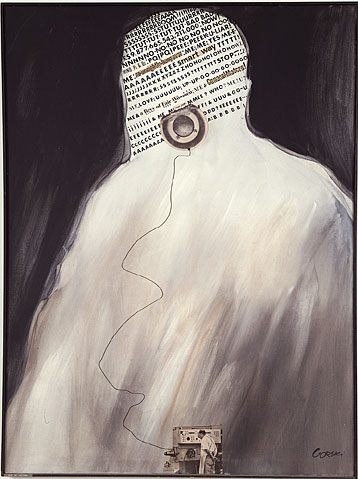

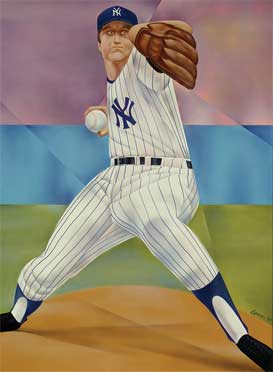

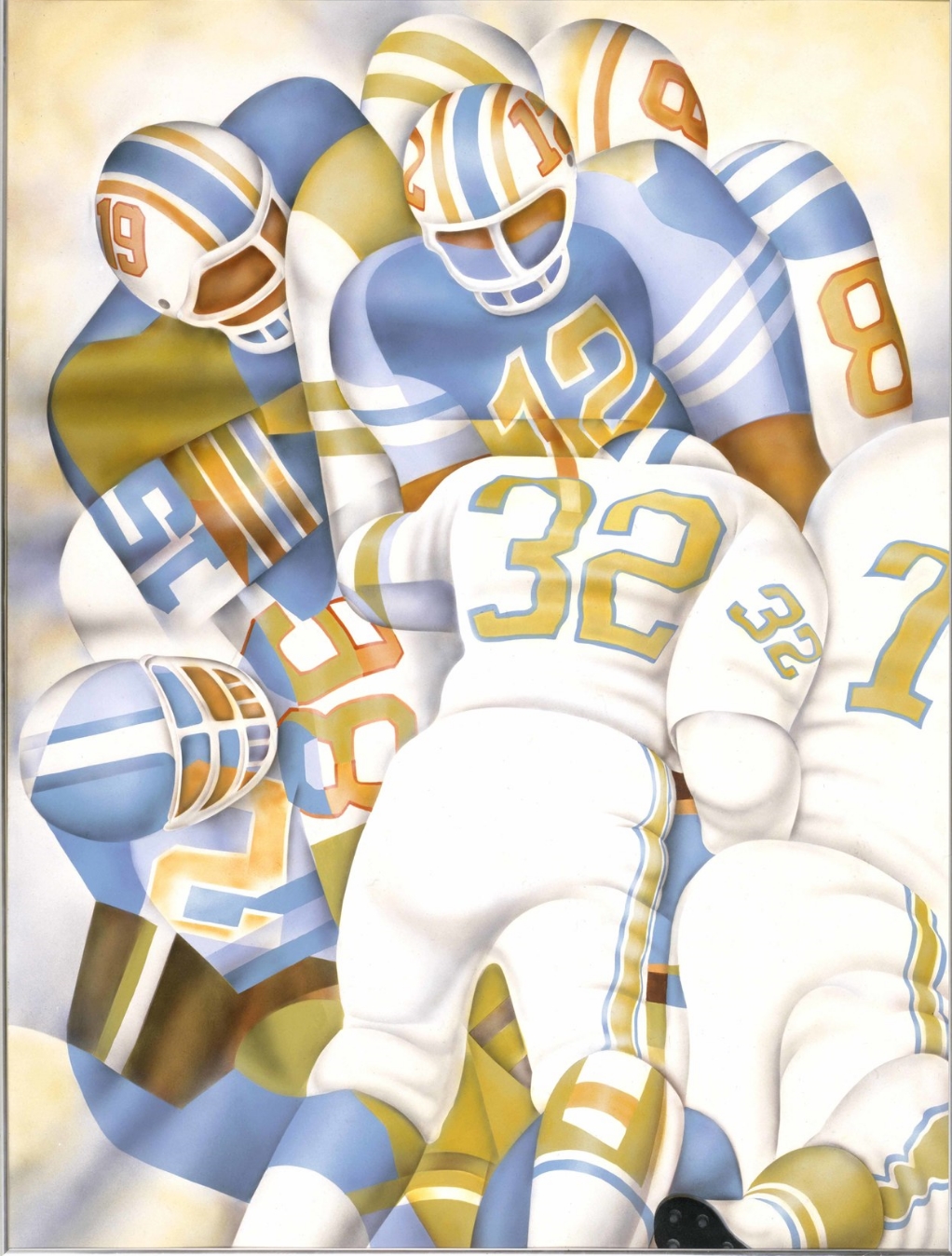

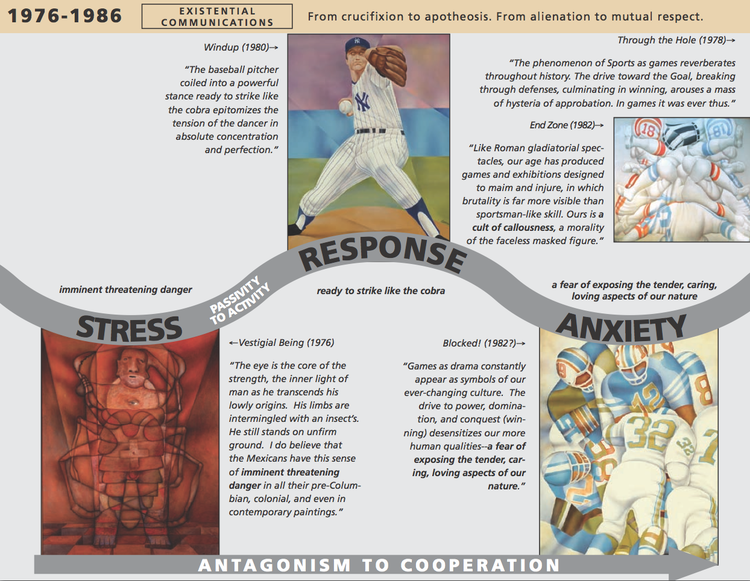

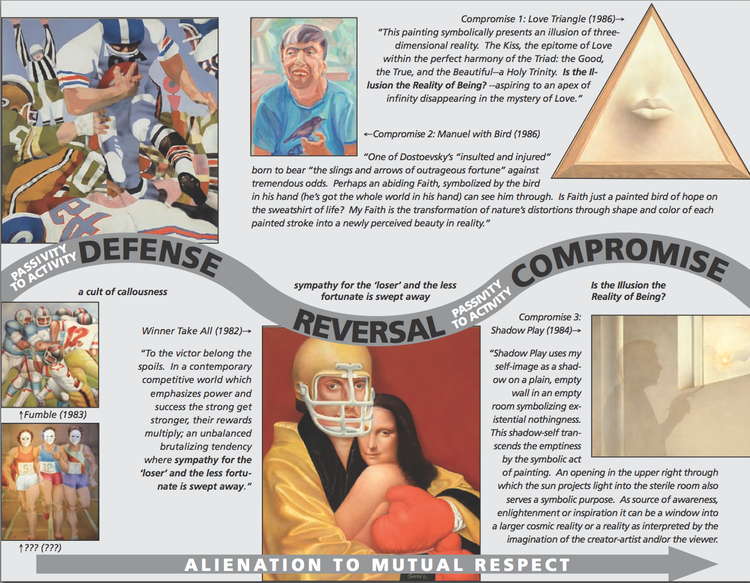

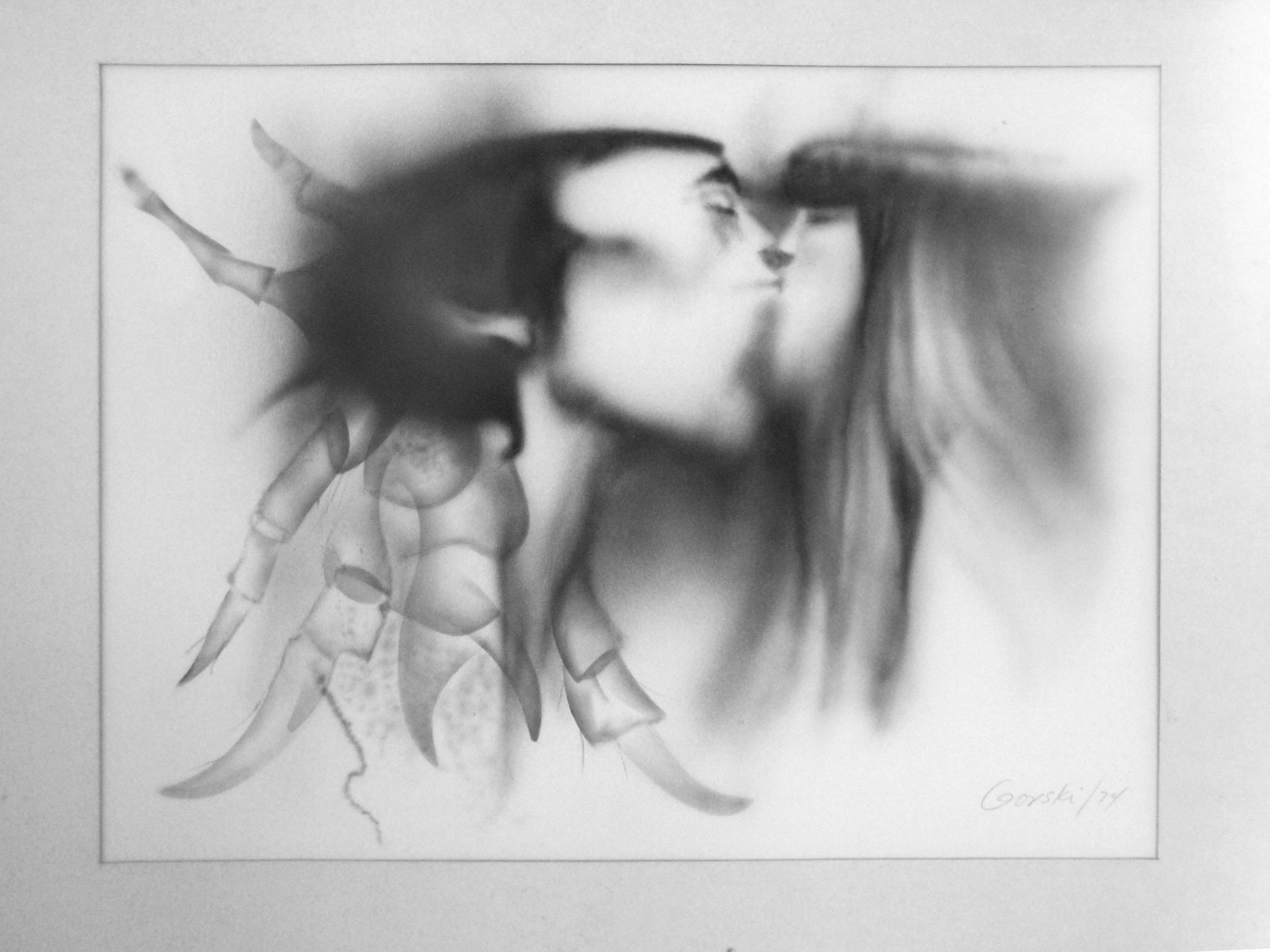

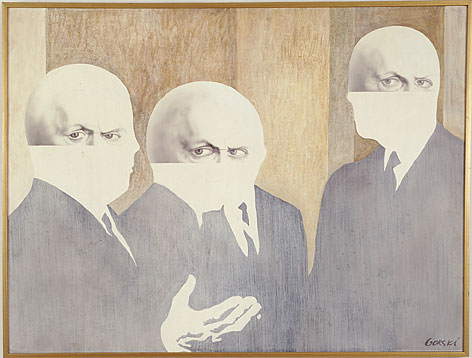

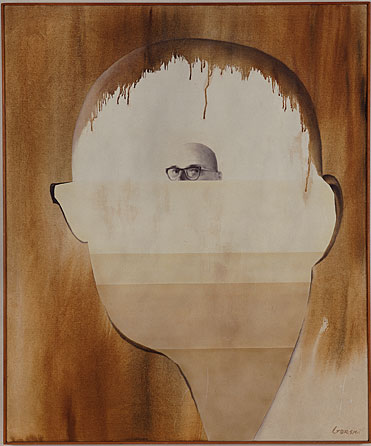

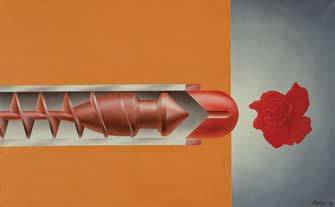

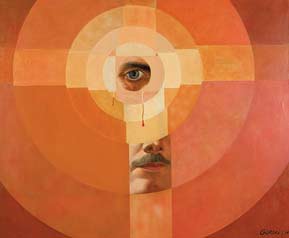

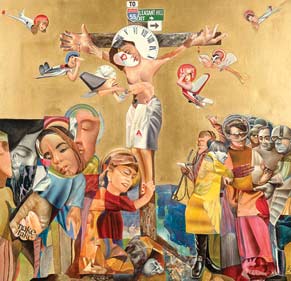

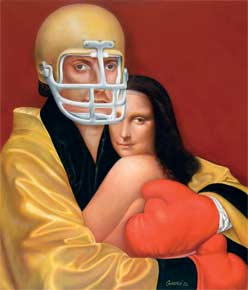

The predominant themes in the artist's preoccupations are with the helplessness of man. Adam first is seen as dehumanized, a victim in a personal struggle with the mistrusted political war machine. Resolving his anger at the Vietnam War, the artist becomes preoccupied with love in the era of the post-war intellectual and societal liberation. The free search for love generates a sense of danger to a married, devout, Catholic man. Temptation and guilt were reflected in his preoccupation with the Crucifix. The artist moved from the theme of the individual sacrifice out of guilt to a new phase of oppression related to losing one's identity playing team sports.

In the final phase of his work, the artist returns to the predicament of his son, who has been diagnosed as mentally retarded. But now, the matured son is no longer a victim, but a winner. In the sequence of the Aberrations of the Creator, Gorski presented studies of men facing the same challenges presented to his son as empowered, sensitive, profound and very respectable individuals. One could say that the artist resolved the conflicts in the Birth and Death of Adam as a submissive person who first felt oppressed and angry, who then became loving, trusting, vulnerable, guilty and self-sacrificial; he who wished to be assertive and bold as an athlete seeks to question the nature of reality. Finally he found himself becoming a self-respecting man reconciled with the creator, despite the challenges that he faced in his life. The saga of Adam is of a proud man whose identity evolved from a chill of darkness to that of the crucifix, to that of Manuel with Bird, evolved to feel humble and sensitive, yet empowered and dignified, respectful of the Creator in spite of his mistakes.

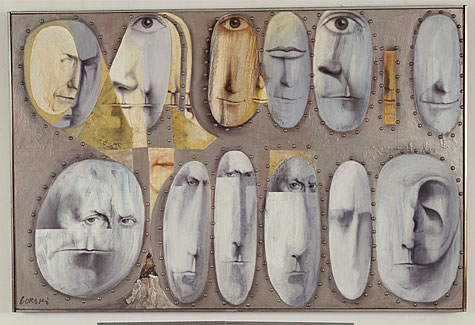

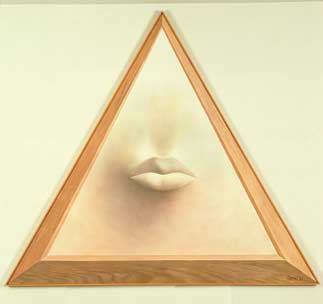

The Gorski paintings are integrated as series of the six part conflict resolution process. Gorskiwhile the canvases of the images of four mouth-canvases reflect the formal alternative ways in dealing with conflict

For more information, please refer to this Gorski site.

Questions to Guide You Through the Gorski Retrospective

All stories, as in drama, movies and novels, begin with a conflict and end with a resolution. We know the plot of stories leading to a moral discovery. Can we look at art and see morality in terms of underlying science?

Since the unconscious composes stories, does art reflect the unconscious? Does it reflect the unconscious as both a scientific and a moral order phenomenon?

Freud described the unconscious as generating conflicts. We describe it as resolving conflicts. Who do you think is right, Levis or Freud?

Since creativity reflects the unconscious, can we study the creative process as the object for the scientific and moral study of the unconscious?

Can we examine the Gorski Retrospective and identify how the artist resolves moral dilemmas? Can we detect in the canvases of Gorski alternative conflict resolution patterns?

Psychology has become a medical specialty diagnosing illnesses as clusters of symptoms. The Formal Theory examines how the mind resolves conflicts as syndromes of six emotions and as relational alternatives. What is personality and how can it be diagnosed?

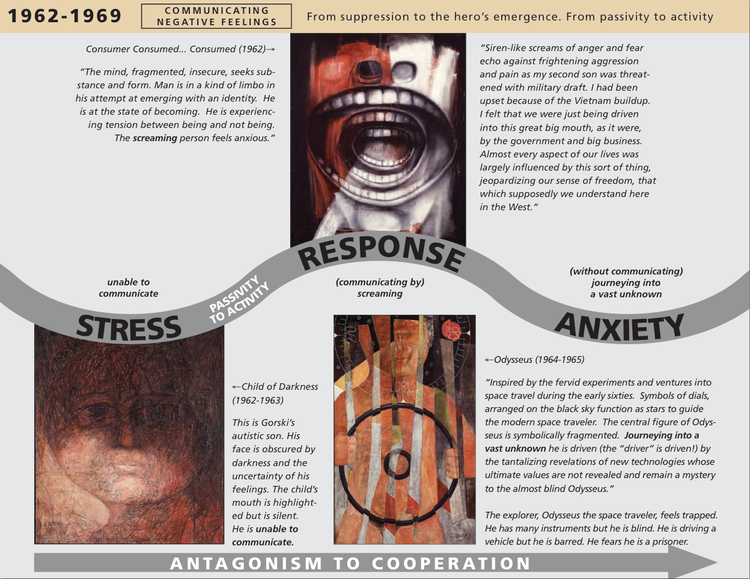

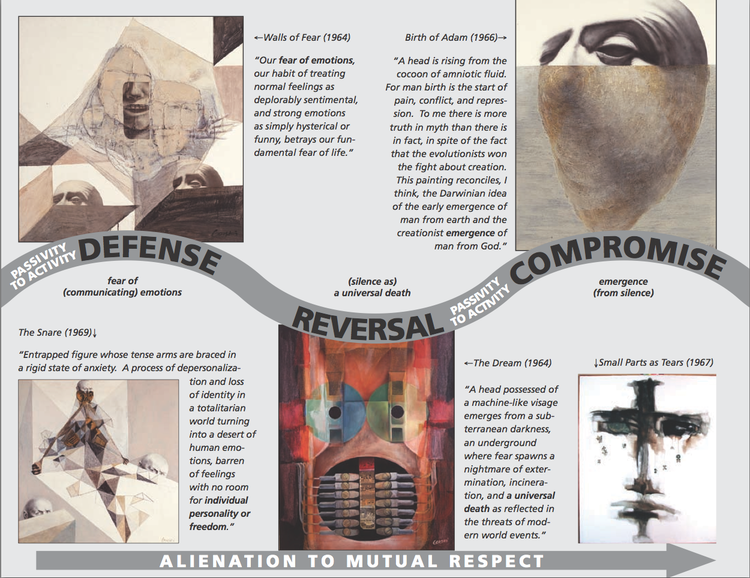

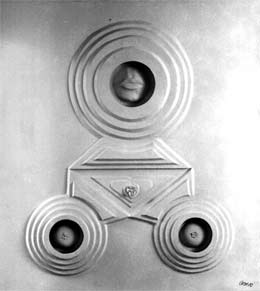

The unconscious emotional process resolves conflict in six-role states of one action. The canvases are connected like a pendulum oscillating in the magnetic field or gravity field of moral alternatives: passive active, cooperation antagonism, and alienation to mutual respect. Gorski’s retrospective features two sequences of conflict resolution. The action in one is the mouth kissing, the action in the second is sports competition canvases. The two sequences of six canvases illustrate how the mind proceeds like a pendulum oscillating three times to reach resolutions as moral discoveries.

Do Gorski’s canvases evolve resolving personal conflicts and do the two sequences improve his emotional adjustment?

Learn how to identify the images of the six role process. Which canvases represent each one of the six role process: stress, response, anxiety, defense, reversal and compromise?

In Gorski’s canvases we can see the alternative ways of resolving conflict. We recognize four types of resolving according to power as dominant and submissive, and according to attitude as cooperative and antagonistic. These alternatives combined lead to four relational modalities. What are the relational distinctions between his four mouth canvases? Which mouths are dominant and which are submissive? Which are cooperative and which are antagonistic?

The unconscious being a natural science moral order phenomenon may be portrayed graphically. Think of the configuration of the sperm and you got the unconscious on the search for moral order. It has a process like a tail propelling it forward, the sine role process. It has a moral compass consisting of directional vectors within a set of circles pointing to the four ways of resolving. Can you portray the canvases of a sequence graphically and their way of resolving by using this type of graphic representation?

HENRY GORSKI'S LETTER TO DR. LEVIS, 1987

“William Blake’s prophetic and apocalyptic poem speaks to our present age of all-pervasive de- humanization: “My mother groan’d! My father wept. Into the dangerous world I leapt”

I leapt out of my mother’s womb in the back room of a working man’s tavern located in a steel town during a world war. My personal odyssey since that traumatic day encompassed half the spinning globe and spanned a depression, another war worth three bronze stars, apprehensions of atomic dissolution as a map maker, still another war which threatened one son, dealing with a severely handicapped hyperactive other son, etc., etc...Painting and art became a defensive shield which cushioned the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” What these “interesting” times (“interesting” in the acrimonious sense of cursing an enemy: “May you live in an interesting age!”) had wrought to my inner person determined the directions my painting would take.

Interest in other cultures dealing with these inward conflicts and bogey men of spiritual under- grounds took me to Pre-Columbian Mexico, mystical Spain and most recently to Italy. The study of Primitive Art experienced first hand in New Guinea, the island arts of the Pacific, Australia and the West Coast, the anxieties of Kafka and Dostoevsky and the mosaics of Italian basilicas established my particular thrust toward expressing and revealing some dimension of the inner person.

A chance meeting, perhaps a natural gravitation, a confluence of opposite attractions (of Art grafting onto Science) has since developed into a fecund relationship. Albert Levis perceived seemingly parallel directions in my paintings as symbols applicable to his Formal Theory of human behavior-- directions of which I was not consciously aware.

My own comments on my paintings in the following text are, to the best of my memory, the sources of inspiration which motivated them. At times there may be differing, even contradictory responses to my work; but that is the multifaceted nature of art--that it can present different aspects, evoke varying responses at different times.

Albert Levis in his formal approach to behavior theory, as seen and interpreted through the artist’s eye, has enhanced the realm of creative vision which I experienced intuitively as a painter. His new dimension of insight fostered a meaningful relationship between the Formalist and the Intuitionist. This manuscript extends the frontiers of understanding our humanity.”